In the course of my artistic development, external experiences beyond the university curriculum have played a crucial role in shaping both my creative direction and my understanding of what it means to be an artist today. These encounters—with artists, technologies, and long-term conceptual works—have sparked new interests and challenged me to expand my perspective on time, process, and innovation.

One of the most inspiring events I attended was a talk and demonstration on AI music creation, covering topics such as live coding, modular synthesis, and machine-generated composition. This session introduced me to the creative possibilities that lie within algorithmic processes, and I became particularly fascinated by the way artists were using live coding not only to compose music, but to perform it in real time as part of an audiovisual experience. Since then, I’ve started to explore live coding environments like Sonic Pi and TidalCycles as part of my own practice, blending randomness and code with performance. This opened up a completely new way of thinking about musical form—not as something fixed and prewritten, but as something constantly evolving through interaction and computation.

Another moment of artistic resonance came from a lecture by the experimental sound artist Victoria Shen. Her unconventional use of circuit-bent electronics, sculptural instruments, and physical gestures offered a refreshing and bold example of how sonic performance can break traditional formats. Her work, full of unpredictability and playfulness, reminded me of the importance of intuition and chaos in art-making. It inspired me to embrace more spontaneity in my own performances and to experiment with the limits of both tools and structure.

A particularly memorable experience was attending a workshop on the Longplayer project, a thousand-year-long musical composition conceived by Jem Finer. When I first arrived in London in 2022, I visited the Longplayer installation at Trinity Buoy Wharf and was immediately struck by the scale and ambition of the piece. The recent workshop gave me deeper insight into how the composition is sustained over time through a combination of algorithmic processes and careful human curation. I was fascinated by the way the project questions our relationship with time, patience, and sonic memory. It made me reflect on how my own work might engage with longer durations and evolving temporal forms, both conceptually and technically.

These experiences helped me move beyond the classroom and into a wider artistic ecosystem, where conversations about sound, technology, and temporality are constantly shifting. They have expanded my sense of identity—not just as a student or sound designer, but as a growing artist participating in dialogues that stretch far beyond any single discipline. Exposure to real-world projects, forward-thinking creators, and unconventional approaches has encouraged me to be more experimental, open, and curious in my practice.

In many ways, these external influences are what help bridge the gap between theory and lived experience. They remind me that being an artist today means staying connected to both the local and global artistic landscapes, being willing to take creative risks, and continuously reimagining how sound can exist in public space and over time.

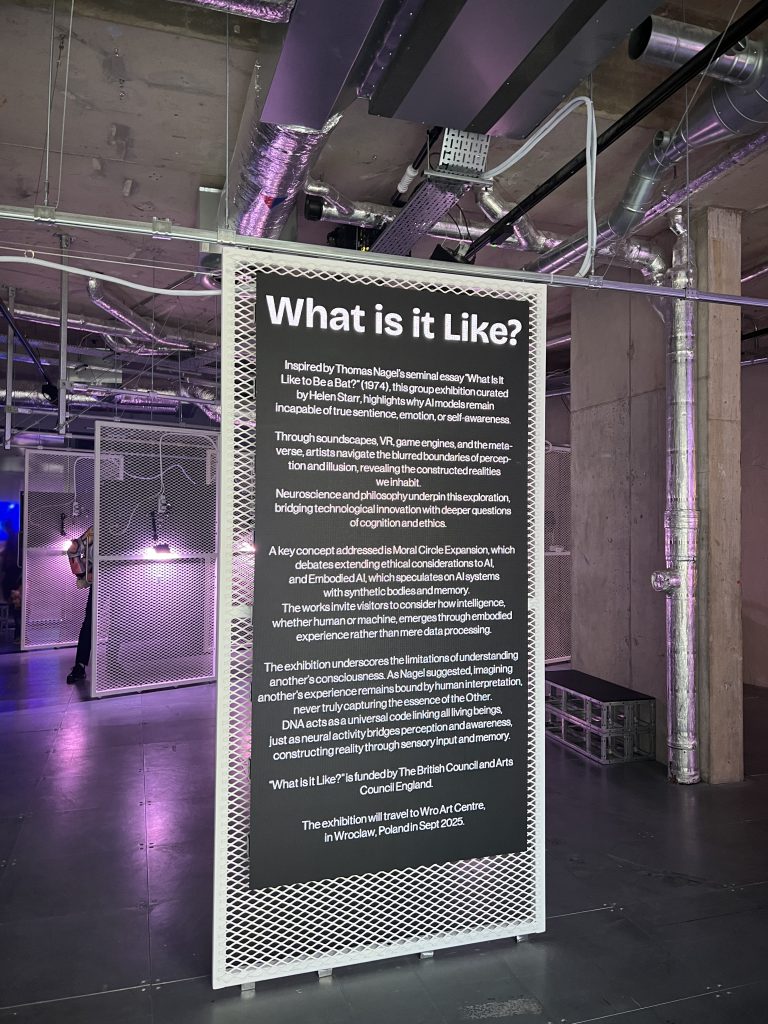

Last month I was visiting the AI art exhibition “What Is It Like?”, a group show curated by Helen Starr that explored the nature of subjective reality, consciousness, and artificial intelligence. The exhibition took its conceptual roots from philosopher Thomas Nagel’s question, “What is it like to be a bat?”, and expanded that inquiry into immersive, multi-sensory environments powered by soundscapes, game engines, VR, and speculative technologies.

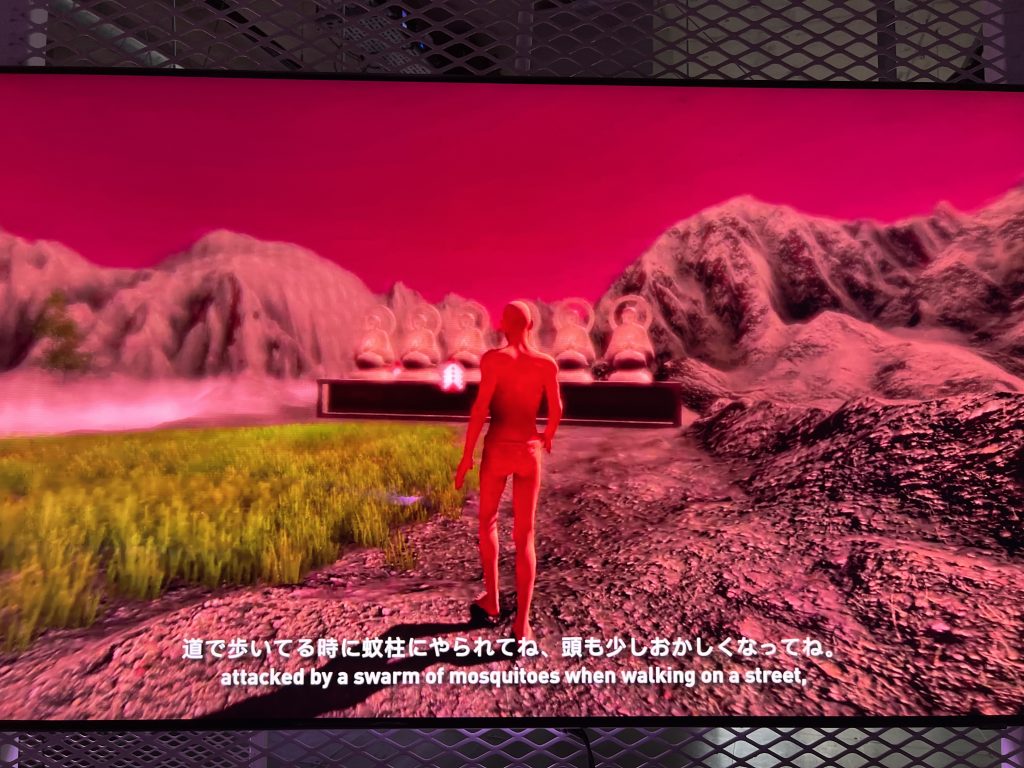

I was particularly struck by how the works reflected on the limitations of AI—not in terms of functionality, but in its inability to experience: to feel, to remember, or to truly “know” itself. It made me reflect on the core of my own sound practice—how sound, unlike static visual images, exists through time, context, and subjective perception. It raised the question: if AI can simulate a sound, can it also simulate presence? Emotion? Memory?

The exhibition challenged me to think more deeply about what it means to be human in the act of listening, and how technologies might mirror or distort that experience. It strengthened my interest in the boundaries between generative processes and embodied experience, and inspired me to continue developing works where sound can act as both a technological artifact and an emotional interface.